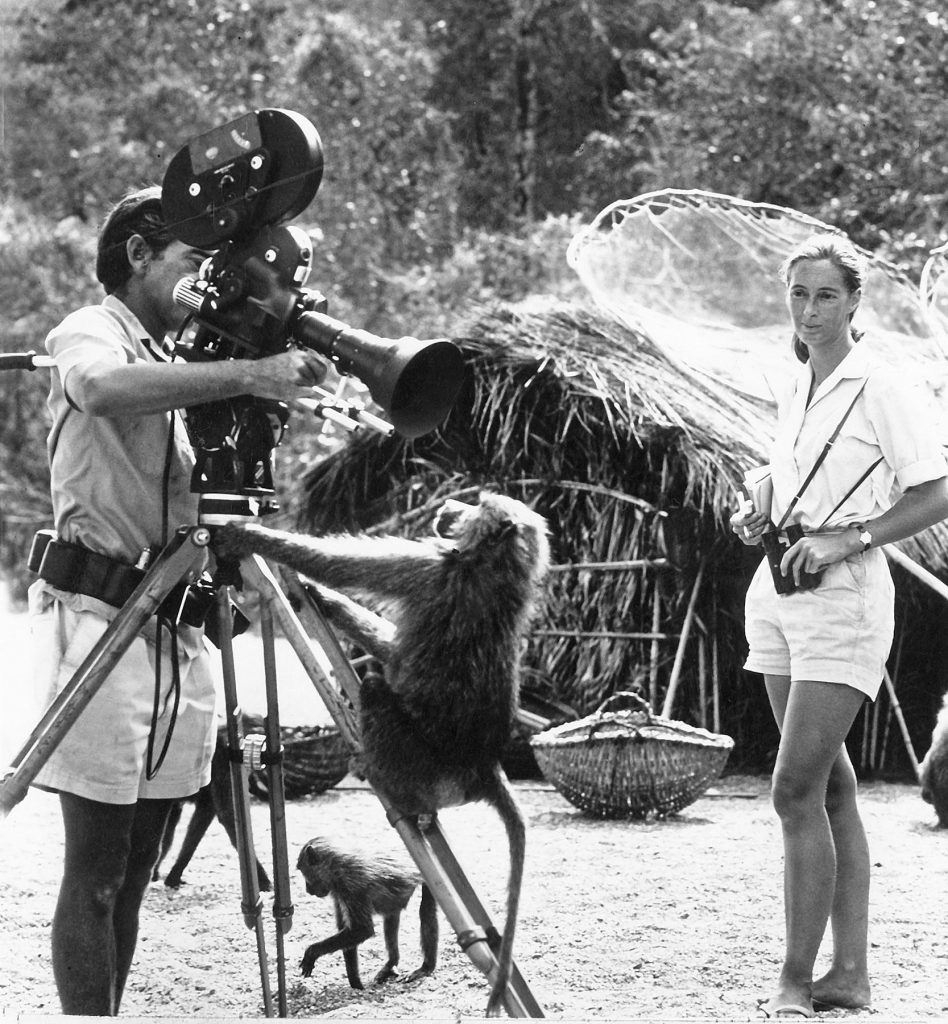

Dr Jane Goodall is considered the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzees. While best known for her research of social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees, she has evolved her passion and activism into a global conservation organisation that not only protects chimps but inspires people to conserve the natural world we share. Dr Goodall’s experiences of leadership, defining moments and having the courage to lead a life with purpose is inspirational. So how did Dr Goodall’s love of wildlife from an early age evolve into a lifetime dedicated to animal welfare and environmental activism? Director of Maximus Brent Duffy spent time with Dr Goodall recently on her Rewind the Future tour of Australia to discuss her amazing life story.

M MAGAZINE: YOU’VE LED SUCH AN AMAZING LIFE. WHERE DID THE STORY OF DR JANE GOODALL BEGIN?

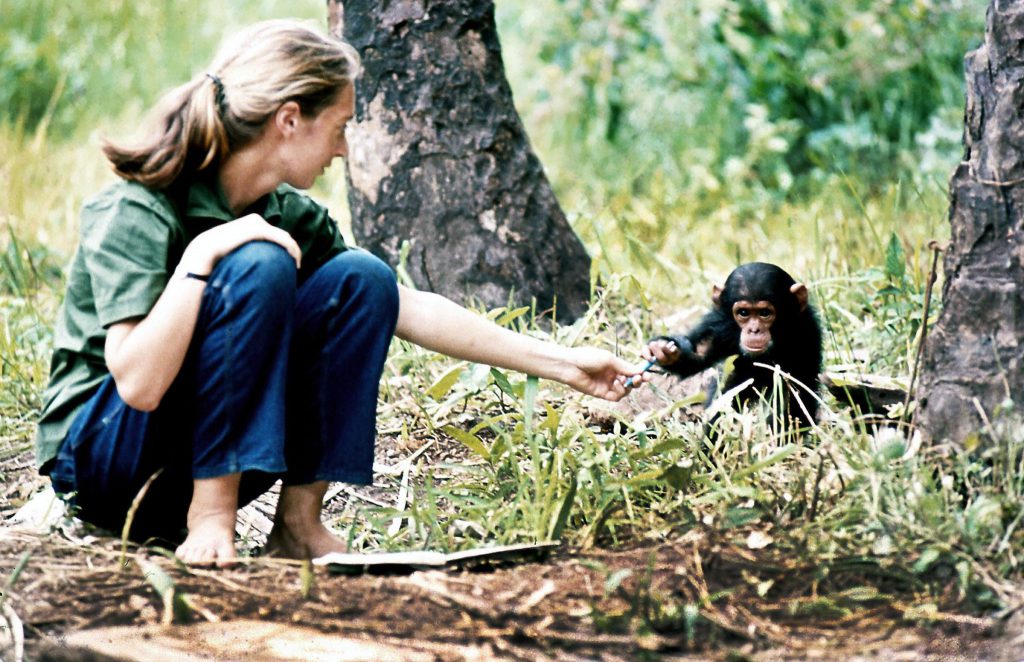

DR JG: I was born in England 85 years ago. My family had very little money and we were living in London, so not too many animals there. But right from the beginning I loved animals. I was always watching them and when I was four my mother took me to the country to visit a farm where I was given the job of collecting eggs. I was very curious as to how the hen laid the egg and decided to wait in the hen house to watch her – it was then that I began my path of discovery. As I grew older, books were my way of learning about life and animals and my mother helped me by finding more books about animals to read. At the age of 10 I found a book called Tarzan of the Apes. That’s when my dream began, I will grow up and live with wild animals in Africa and write books about them.

MM: WHAT ROLE DID YOUR FAMILY PLAY IN PROVIDING SUPPORT IN YOUR FORMATIVE YEARS AND CAREER?

DR JG: My mother was a huge support – she was ahead of her time. On the day I waited for the hen to lay her egg I had been missing for many hours – even the police had been called. Instead of getting angry, my mother saw the light shining in my eyes upon my return and sat down to hear my wonderful story of how the hen laid its egg. In later years that same amazing mother supported me by volunteering to accompany me on my first trip to what is now known as Tanzania. She was a huge boost to my morale, telling me, “Jane, you’re learning more than you think” when I felt disappointed at my lack of progress.

MM: WHAT WAS YOUR BIGGEST CHALLENGE WHILE ACHIEVING YOUR PURPOSE DURING YOUR CAREER?

DR JG: One of the chimpanzees I had been observing, David Greybeard, used leafy twigs as a tool to access termites in their mounds. At this time science had decided that humans, and only humans made tools. Of my observation many scientists said, “Why should we believe her? She’s just a girl, she doesn’t have a degree. Girls aren’t supposed to do this sort of thing.” So, after being in the field for two years I was sent to Cambridge by Dr Louis Leakey, and despite not having attended college previously, my first degree was a PhD in ethology. I didn’t even know what ethology meant! I was nervous of my professors and told by many of them that I’d done everything wrong. I shouldn’t have named the chimpanzees and could not talk about them as having personalities, minds or emotions. Today, however, it’s such an exciting time to be in the world of animal behavioural studies – we’ve learnt so much about the intelligence of many animals and understand that just like us, chimpanzees have emotions like happiness, sadness, fear and despair. It’s become more and more obvious that there isn’t a sharp line divided between us and the chimpanzees as was originally thought.

MM: WHEN YOU WERE FACED WITH THE CHALLENGE OF DISBELIEF AND DISENGAGEMENT, HOW DID YOU FIND THE COURAGE TO CONTINUE YOUR PATH? WHAT MOMENT GAVE YOU THE COURAGE TO WORK TOWARDS YOUR FUTURE?

DR JG: Back in 1986 I assisted in organising a conference which brought various scientists together to discuss whether chimpanzees exhibit different behaviours in different geographical locations. At this conference I learnt of the cruel practices which medical research and circus-trained chimpanzees were exposed to. I also learnt that all the forests we were studying chimpanzees in were disappearing. I went to that conference as a scientist, planning to carry on with this beautiful life, but I left as an activist. I didn’t make a decision, I just went as one and left as another. This was the beginning of a long fight, which ended four years ago, when the Director of the National Institutes of Health in the US agreed to release the chimpanzees used for medical research in America. It was a very long and hard fight, which luckily many other people joined.

MM: AN IMPORTANT MESSAGE FOR LEADERS IN TODAY’S RAPIDLY CHANGING WORLD IS TO BE PRESENT AND EVOLVE HOLISTICALLY. YOUR ACTIVISM HAS EVOLVED INTO ENVIRONMENTALISM ON A GLOBAL SCALE – WHAT INSPIRED THIS SHIFT?

DR JG: After achieving my PhD I went back to Gombe in Tanzania and built a research station. Out in the rainforest, I learned everything was interconnected and that each species, no matter how small or insignificant, could make a huge difference if it became extinct. It was apparent that the loss of one species could lead to an ecological collapse. I also learnt about the plight faced by so many of the African people living in and around chimp habitats: the crippling poverty, the lack of good health and education facilities. That’s when it hit me that if we don’t do something to improve the lives of the people, then we couldn’t even try to save the chimps. We sent in a local team of Tanzanians who sat and listened to the Africans asking them what we could do to help make their lives better. From here we worked with the local government to improve education and health facilities, return fertility to overused farmlands without chemicals, introduce water-management programs, scholarships for girls and micro loans for environmentally sustainable projects. From here there was no going back.

MM: AT MAXIMUS WE TALK ABOUT LEADING WITH PURPOSE. WHAT IS YOUR MESSAGE TO BUSINESS LEADERS AMID THE ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES TODAY?

DR JG: I’ve met many young people who seemed to have lost hope for the future; they feel that older generations have compromised their future through the use of fossil fuels, excessive pollution and waste. But I don’t think that it’s too late, I have hope. We have a window of time, but we cannot be bystanders and if we use our amazing brains now, we can find a way to live in greater harmony with nature.

[FACT]

The Jane Goodall Institute under a microscope:

- More than 5000 primates projected in JGI habitats

- 130 communities supported worldwide

- 5000 projects led by young people as part of her Roots & Shoots program

MM: AFTER ALL YOUR YEARS STUDYING CHIMPANZEES, WHAT LESSONS DO YOU THINK HUMANS COULD LEARN FROM THEM, ESPECIALLY IN REGARDS TO LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOUR?

DR JG: Some chimpanzees strive for a high position in the dominance hierarchy more than others. They swagger and bristle, making themselves look big and strong – which reminds me tremendously of some politicians today! However, only one of them will get to the top, and it’s those who use their brains and form alliances, not aggression, that last the longest.

This article was originally published in the 3rd edition of M Magazine, an exclusive print magazine aimed at inspiring and driving change through Australia’s executives and heads of HR.