For many years, ‘move fast and break things’ was gospel in the tech industry. Facebook’s classic mantra represented a philosophy of trying out new ideas quickly so you could see if they survived in the marketplace. If they did, you refined them; if they didn’t, you could throw them away without blowing more time and money on development.

That approach was ideal for a world where digital technologies were exploding into popular usage. Software engineers could deploy fast, safe in the knowledge that it was just code and that any mistakes or bugs could be fixed on the fly. A generation of startups swallowed the principle whole and an entire industry of consultants and soundbytes came to life.

Today, a new class of technologies is emerging that’s calling that mindset into question. We live in a world where ‘digital’ is no longer a glorified marketing department in a company, or an economic sector on its own, but a layer over everything. Every business, every industry, must have some level of tech investment to be successful, and the C-suite are not immune. More than half of humanity is now online, using the internet every day.

And as digital shifts to a cognitive space – where building tech requires decision-making and consequential thought – design decisions that may have seemed trivial can turn out to have significant and irreversible consequences further down the line. ‘Don’t be evil’ and ‘move fast and break things’ served their purpose for a while, but it doesn’t exactly have the same ring. Maybe their replacements could be, ‘Is this algorithm toxic?’.

Traditionally, code has always been relatively harmless. Daily interaction with pain, physical harm or death was a lot less likely if you were working with bits and bytes than if you were working with human bodies (medicine) or heavy machinery (transportation). In order to fulfil the ethical warrant of the profession, all you had to do was make the product work. It was up to other people to figure out the applications or the social mission. That’s no longer the case.

Developers still seem a little baffled when told that the systems they’ve built (systems that are clearly working very well) are corrupting the public sphere. In part, this is due to the newness of the industry. Doctors, for example, are technical people too, but they’ve been trained on a code of ethics developed over a very long time: first, do no harm. The tech sector has had a different ethos: build first and ask for forgiveness later. Now leaders are being called to account, as a result of becoming too powerful and too dangerous, too quickly.

Business and business leaders leaning into a more technology-based direction need to do more than acknowledge criticisms; they need to be accountable and start taking responsibility for our actions. We need to move beyond the obsession with customer experience and usage metrics, and start thinking about how to serve society in general. So how should we approach software development in the future? Ironically, the answer might be found in industries that have been criticised for being slow and old fashioned. Engineers can’t afford to build bridges with design flaws. Doctors can’t prescribe the wrong medicines and then fix their mistake a few days later. Airlines can’t launch a product with 90 per cent assurance. Anyone who has technology development in their remit would do well to take a leaf from their book, and today, that means all leaders.

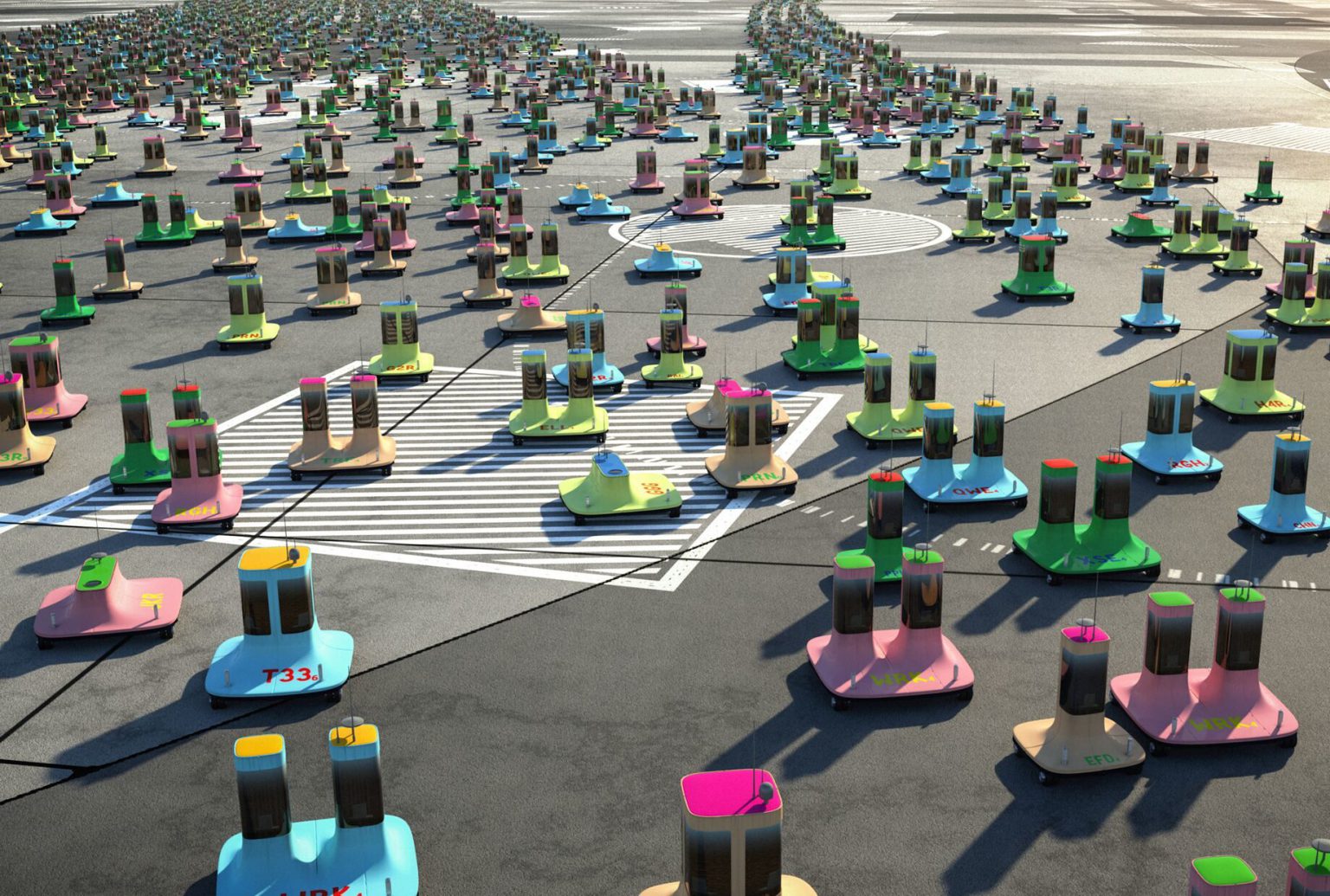

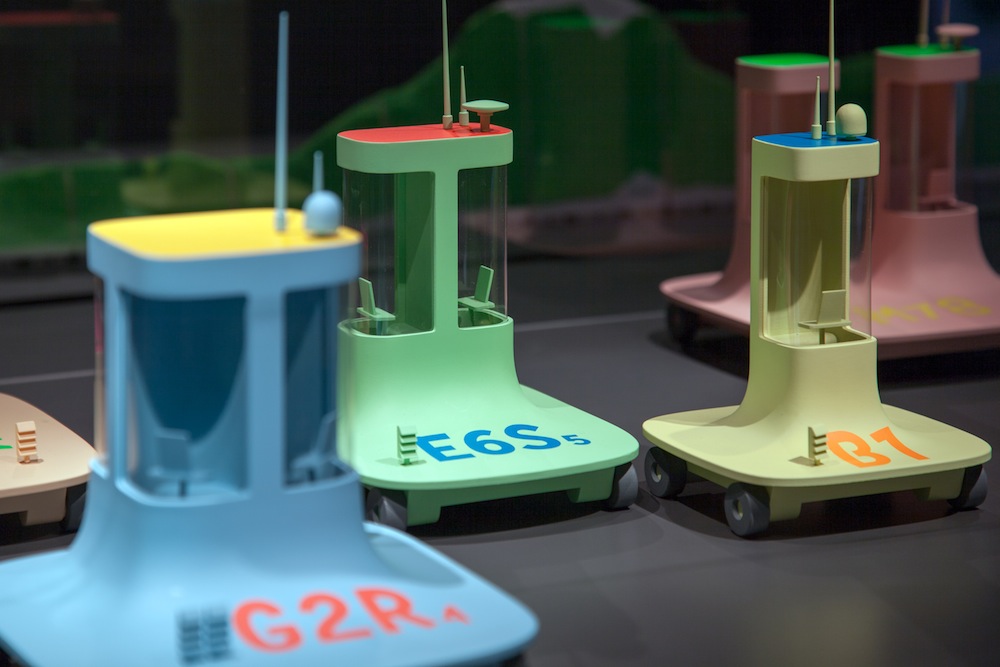

The Digiland experience: In these photos, designer Anthony Dunne and architect Fiona Raby have envisioned a world of transportation based around the Digicar, a self-driven vehicle whose focus is less around getting from A to B and more on ‘navigating tariffs and markets’. Every inch of road and access has been designed and coded in a digital language to achieve optimal results, from environmental impact to travel time and productivity.

This stuff isn’t sexy. Technicians and pilots, for example, are forced to step through an exhaustive, boring and very predictable set of instructions before every flight. You certainly won’t see that in the decks of thought leaders at expensive conferences on innovation – but it’s time those at the helm started. A boring checklist is effective. All the debate happens before something gets added, not at the end. Which means when you’re about to launch a product, design a program to take your employees to the next level (or take off from a runway) you need to worry less about implementation and more about process.

Good development-focused organisations do this as a matter of course. At Apple, they have an internal checklist that goes into great detail about the process of releasing a product from beginning to end, from who’s responsible to who needs to be looped into the process before it goes live. Even before a team starts working on something, they make a checklist to prep for it. Do we have appropriate access to development and staging servers? Do we have the correct people on the team? When you’re done, you check it off. Easy to collaborate on, and easy to understand.

Ultimately though, there is still an underlying problem. Facebook, for example, changed its motto in 2014 to ‘Move fast with stable infra’ (catchy, right?) implementing more automated tests, better monitoring and extra infrastructure to help identify bugs as early as possible. None of that helped them when fake news, election hacking and data privacy blew up in their faces.

The problem wasn’t technical – it was cultural. Engineers at the company simply weren’t able to conceive of use cases where their product could be abused by people who didn’t share their worldview.

That’s why the next generation of technology people and those executives leading the way need better training. Leaders need to be prepared. Medical students spend a lot of their undergraduate years being taught to think critically about the ethical implications of their decisions. The same should be true of anyone with technology development in their remit. The good news is that this does seem to be slowly happening. Microsoft researchers have written a Hippocratic Oath for artificial intelligence (AI), and Stanford University, the academic heart of Silicon Valley, is developing a computer science ethics course to train new technologists and policymakers.

Ultimately, the safest bulwark against baking bad ideas and flaws into code is diversity. Groupthink is a deadly enemy in a world of hyper connectivity, exponential technologies, and unintended consequences. Diversity mitigates it. The ability to draw on contrasting worldviews, and to run ideas through teams that differ across gender, age, political affiliation, race, neurology, class, profession and cultural background ends up building far more robust products that do less harm once unleashed upon the world.

We know these are aims shared by the vast majority of people working in tech. It’s an industry united by a belief that digital technologies are a remarkable tool for improving human lives in a truly transformational manner.

[FACT]

More than half of humanity is now online, using the internet every day.

WHAT NEXT?

Laura Sturt-Addicott, Associate Director at Maximus, says it is important that leaders take the proverbial bull by the horns, proactively creating the right teams and displaying a solid moral direction. Here’s what you can do…

Laura Sturt-Addicott believes some incubator labs need to come with a warning: ‘display only’. “Free experimentation is absolutely essential for innovation within technology to occur,” she says. “We’ve seen companies create a lab and say, ‘Innovation now exists in our organisation, we’ve ticked the box, we’ve got some virtual reality (VR) headsets and we’re done’. It doesn’t work like that.

“Future-focused leaders need to be a part of it. They’ve got to be just as curious as the tech people.” But, Sturt-Addicott warns, as tech becomes more and more necessary to business success, the digital industry, those developing automation and the leaders responsible for rolling it out should be thinking a lot harder about the ethics behind the build.

PROACTIVELY CREATE A DIVERSE TEAM

“Alongside the plethora of benefits to having diverse teams, a mix of thinking styles will defend against groupthink, bias (conscious and unconscious), and help provide a more holistic picture of the risks inherent in technology development. As well as protecting against these areas, greater diversity increases innovation and increases capacity to ‘disrupt’ the business internally. By creating diverse teams and giving the appropriate psychological safety in the workplace, leaders will be significantly better equipped to manage innovation and technology advancement, among myriad other things.”

DISPLAY ETHICAL CONSISTENCY OVER TIME

“When faced with developing technology with a broad impact, teams will look to their leaders, consciously or unconsciously, for an indication of the organisation’s moral compass. By placing a firm and consistent view on ethics, front and centre, when developing technological solutions, the whole organisation will understand the importance of responsible development.”

ASK THE RIGHT QUESTIONS OF YOUR PEOPLE

“When it comes to technology development, leaders need to know enough to ask the right questions. Can we ensure the privacy of this data? Who owns it? Have we confirmed we aren’t disadvantaging a group with this technology? What’s the longer-term impact of this? If this product is successful how does it look in five years’ time? Demonstrating an understanding of the longer-term impact is critical.”

THE VALUE OF REFLECTION: SOMETIMES THERE IS NO ‘UNDO’ BUTTON

“When leaders and organisations move quickly to meet demands or rush to put out a new update to a product or a new idea to market, most often the aim is to be as fast as possible. With the increase in adoption of exponential technologies, this means any errors or bias can be amplified.

“A recent APRA report as part of the royal commission specifically calls out issues in reflection and introspection. Leaders need to take the time to stop, think and talk through unintended consequences, to bring diverse teams together and set the tone. Carving out time to get this right is critical. With some decisions and technology there is no undo button. Leaders must be aware of which areas are non-negotiable to ensure ethics and success are bonded together.”

A huge amount of effort and thinking goes into every article we publish and we’d like to say thank you to Dr Angus Hervey for contributing to this article

This article was originally published in the 2nd edition of M Magazine, an exclusive print magazine aimed at inspiring and driving change through Australia’s executives and heads of HR.

Related Insights

The Changing Landscape of Sales Leadership

On my recent holiday I read Dan Pink’s new book, To Sell is Human. The chapters argue the growing importance of sales skills in both traditional and non-traditional sales roles. Dan’s perspective runs against the viewpoints of many that believe the art of sales is in decline. In a world full of information that is so easily accessible through technology, many think digital and social marketing is replacing the role of the traditional “salesman”

4 Essential Behaviours of Modern Leaders

Your management style is a reflection of your personal strengths, weaknesses, attitudes and the values that you have build up over the course of your life. Because of this, there are as many kinds of leadership as there are leaders. From the autocratic to the democratic, from the conceptual to the task-oriented, managers come in all shapes and sizes – with varying levels of effectiveness.

Performance Management Has Failed

Human resources has gotten caught up in a flurry of systems and processes. That overzealous desire for order and regulation belongs anywhere but in an organisation’s social hub. Excuse the psych jargon, but this is a prime example of Stratified Systems Theory. In other words, processes that are fundamentally human are getting policed with too much structure and complexity, making them disorienting and ineffective.