There is no question, what we learn, and how we learn, is under scrutiny. As organisations and governments look to tomorrow’s graduates to provide the leaders of an increasingly complex future, schools and universities along with organisations, are seeking more progressive solutions to better equip the custodians of tomorrow.

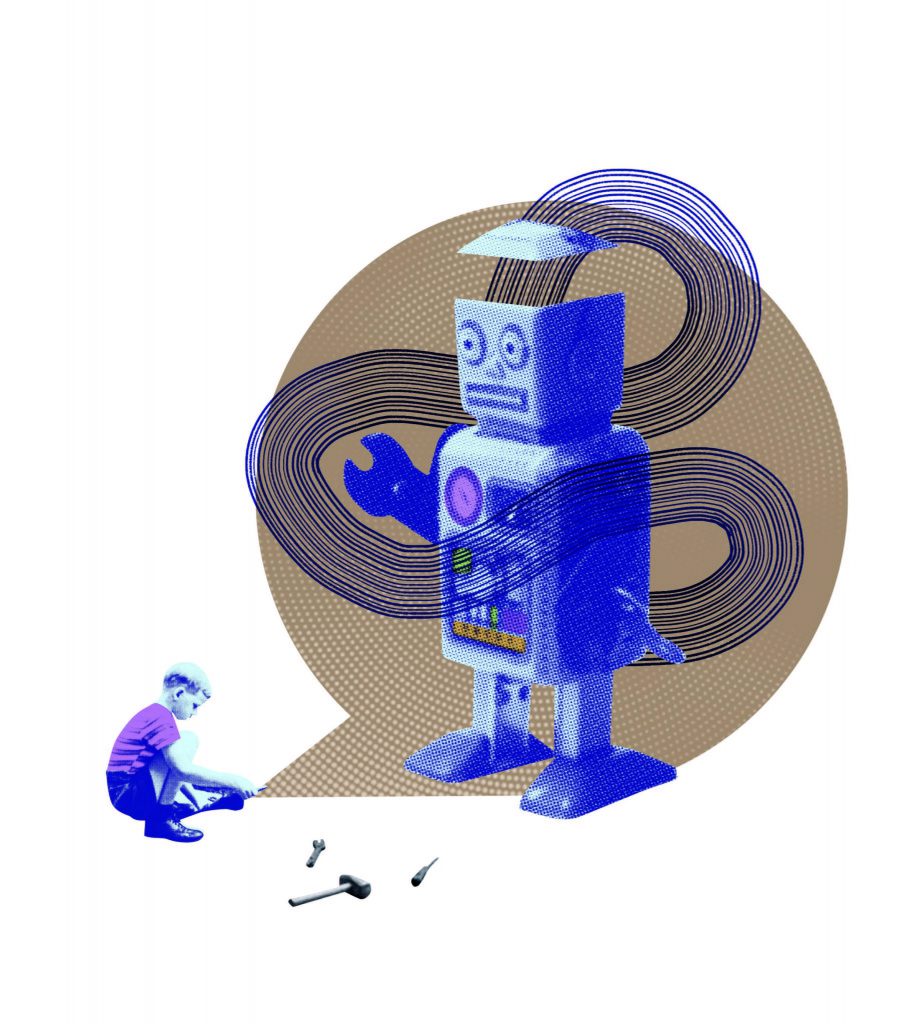

The internet has already hugely changed our schools, workplaces and social structures over the past three decades. Today’s rapid development and adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) is set to revolutionise society once again. Machines that can learn and will become more skilful over time, robots that can replace humans in most repetitive physical tasks and ever-faster spread of information, are likely to wipe out about 40 per cent of today’s jobs within the next two decades.

So, what jobs will replace those that the robots have taken? And are our educational institutions ready to deliver humans who can think, learn and adapt sufficiently to survive the coming onslaught of technological evolution? Navigating the progressive complexity of our world requires ever-increasing levels of educational achievement, “to be in control of one’s own life, to understand one’s culture, to participate meaningfully in democracy, and to find fulfilling work,” according to Emeritus Professor Dylan William of University College London.

The leaders of tomorrow must meet even higher expectations and adapt to a way of learning going forward that is different from today. They must harness nuance and curiosity to hold their place in a world where AI and machine learning deliver many of the outcomes currently furnished by humans.

“Most of the organisations and industries we partner with are going through various degrees of disruption; they are looking at ways to make sure their leaders are able to deal with that disruption,” says Associate Director at Maximus Dr Nora Koslowski, who works with organisations, including universities, to create and develop the leadership behaviours and mindsets to future-proof Australian leaders.

“Most forward-thinking organisations want their leaders to go further than just dealing with disruption: they want them to be active in driving transformation and to be confident in their ability to navigate through disruption,” she says. “They need their leaders to be future-fit.”

It’s time for organisations to step up to the plate and stop expecting fully trained graduates to land on their doorsteps, she adds.

Business needs to be better at engaging with education, offering more paid trainee placements for university students that tie in with their degree demands, providing better feedback to course co-ordinators about what students need to learn and what they can contribute, and developing and training their own leaders within the workplace. But educators also need to move a lot faster if they are going to deliver on the changes that our society needs from our school and university students when they enter the workforce. Tomorrow’s graduates will need to hit the ground running – or they won’t be able to keep up.

“A lot of universities recognise that the traditional, linear model of learning is dying out.”

– Dr Nora Koslowski, Associate Director at Maximus

LEARNING HAS TO CHANGE

Mark Sowden, Director at Maximus and former teacher who leads our Melbourne business, says that the traditional approach to learning in both schools and universities, and the way that it is assessed, is not the right approach to deliver the key skills we need for the future.

“There is recognition that school-assessment processes need to shift. Progressive approaches to assessment seek to embrace recent evidence in relation to the development of curiosity and encouraging passion for learning,” he says. “The bell-curve to measure achievement is no longer a meaningful way to determine student engagement and a learning mentality. The forced bell-curve system to measure ATAR in schools goes against everything we know about developing curiosity and encouraging a passion for learning rather than putting boundaries around it.”

“Universities understand they need to evolve,” continues Sowden. “Delivering content in isolation of curriculum that builds the mindset and self-direction needed to succeed in tomorrow’s workplace is no longer a viable educational strategy.” That has to change, he says. “Universities need to instil in their students a passion for being curious, and ensure people seek to understand and find the nuance in what they comprehend.”

“There are a range of barriers inherent in the university structure with the potential to inhibit growth,” Sowden notes. “Research-intensive universities face substantial pressures to seek and obtain competitive grants for their research. The balance between research and teaching innovations has never been more apparent. I am passionate about supporting these important institutions to evolve a more progressive focus that adequately supports the growth of our emerging generations. Universities have played a key role in our history and they should play an evolved, progressive role in our future.”

University in the age of smartphones, Google and broadband internet is a very different beast, says Associate Professor James Downes, who is the Associate Dean (Learning and Teaching) at Sydney’s Macquarie University. Downes says that it’s an exciting time to be in education. But there is important work to be done to bring everyone together on the same page, he says.

“Students don’t comprehend that they need to develop deep skills in particular areas if they are to succeed,” Downes says, adding that being able to Google answers to anything has changed the way learning is approached.

The role of the academic has evolved too, he says. Instead of delivering information or content in a lecture environment, their role is now to help students understand what they need to learn.

That can involve knowledge and technical skills, but also ‘softer capabilities’ that are critical in the workplace, such as working in teams, strategic and big-picture thinking, and looking forward.

“Students now have access to information, quite literally, at their fingertips; but being able to find things on the internet is no longer a valuable or unique skill,” Downes says.

“In a knowledge-rich environment, valuable skills will include the ability to connect facts together in a long sequence to reach conclusions, and to look through a whole field of uncertain information and draw an uncertain conclusion – to prepare a strategy based on experience and insight.”

Downes says that students need to leave their education with a much more diverse set of skills. He now helps teaching academics bring these soft skills in a “controlled and systematic way” into their programs.

Macquarie University is providing professional development for academics so they can gain confidence in how to change the way they teach, he says. It’s method, not content: “You don’t get to be a successful academic at a university without having most of these skills anyway,” he adds.

Big shifts in education must happen faster. Producing tomorrow’s leaders means schools, universities and organisations must collaborate differently, each altering their approach to teaching and learning, towards different outcomes, Sowden says.

“We need to address the mindset and the ability for people to learn, and activate their intrinsic ownership over their own learning rather than sit in a classroom and be told the answer,” he explains.

SCHOOLING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR FUTURE LEADERS

Leading educator Leslie Loble, now Deputy Secretary of the NSW Department of Education, points out that the demands of the 20th-century workplace shaped education in both schools and in universities, delivering graduates with a bundle of skills and knowledge that could be applied in their employment. But this skill set is no longer essential in our digital workplaces, when everything we need to know is available at the stroke of a single key.

“Machines are acquiring those skills as we speak, and we are swimming in a digital sea of information,” she writes in the book Future Frontiers, which explores education and AI.

Mark Scott, former ABC chief and current head of the NSW Department of Education, also makes note in Future Frontiers that in schools, the fundamentals won’t change: literacy and numeracy remain the foundations of learning. Scott strongly disagrees with the argument that discipline knowledge is redundant in the age of the internet. “Strong discipline knowledge is essential to deep understanding, strong thinking skills and the ability to learn,” he writes. Schools must lift expectations and free up space so students can “delve deeper, to inquire as much as to answer and to apply their knowledge to real-life contexts,” he continues.

While we cannot predict the future, and the exact skill requirements of employees of the long range, we do know the type of learners that we want to develop through schooling – students who are critical and reflective, open to a lifetime of learning and relearning, who are comfortable with change and have empathy and a global outlook, says Scott.

CHANGING THE WAY UNIVERSITIES TEACH

Koslowski says that higher education is undergoing an important transition, and in most areas has acknowledged that people now learn differently. Leading to the thinking, universities must now work with organisations in a different way.

“A lot of the universities recognise that the traditional, linear model of learning – where you go to university, secure your qualification, and you’re set up for your career – is dying out,” she says. “The death of these traditional pathways has been accompanied by a better understanding of how humans learn best – and it’s not by delivering a lecture or content, memorising it then applying it.”

The ‘YouTube’ generation has brought about a change in learning, where people access micro chunks of information as, and when, they need it. She cites Masterclass – where, for a small fee, online courses from the best in the business are available to a broad audience. “This has challenged universities to think about how they engage with learners differently, because they are no longer competing just with other universities, but also with the likes of YouTube.”

While universities want to build curricula to equip graduates with the right skills, they typically take years to develop these, working off very different timeframes and speaking a very different language to most corporations, Koslowski points out. Partnerships with tertiary students and industry, earlier in the curriculum development phase, along with speedy updates to degrees, are two important changes that the sector needs to embrace, she says.

Sowden believes that universities must also reposition themselves from having transactional one-off relationships with students to staying relevant and maintaining ongoing interactions through lifelong learning; and from delivering content-rich degrees, to developing long-term abilities and future-fit mindsets. “To achieve this, universities will need to look outside more for their answers,” Sowden says. “In the work we are doing with universities the focus is on more collaborative, more innovative and more curiosity.”

Engaging with industry is a key to this revolution and something that Maximus often facilitates, he adds. Koslowski agrees, and points out that industry and universities are in charge of a talent marketplace for the Australian economy. “We all have a common goal of developing the people who have the right skills to lead us into a prosperous future,” she says.

ADOPT A ‘ROOKIE MINDSET’

For some years, organisations have been rethinking the way they develop their employees and their leaders – switching from training skillsets to changing mindsets, to prepare their people for a new, fast-moving, AI-dominated business world, says Vanessa Powell, Associate Director at Maximus. Building curiosity and courage in employees is a critical part of changing mindsets for the future, she says, adding, “Companies will need their people to lean into challenge and to be comfortable in the unknown.”

There’s a lot of ‘unlearning’ that needs to take place too, Powell adds. “That means letting go of some of the approaches that got them to where they are today, and being comfortable to adopt a ‘rookie mindset’ – the idea that they can be a learner, rather than the expert. They don’t always have to hold the right answer,” she says.

A ‘rookie’ makes allowances for their knowledge gaps and works from the basis of asking great questions. They have the permission to make mistakes but learn quickly, Powell explains. “They don’t expect all the answers to come from their ‘domain’ of knowledge; rather they will be able to integrate and value different viewpoints and expertise from different subject areas.

“Leaders need to leverage diversity, taking competing views and synthesising new solutions to appeal to a multi-varied customer base from a range of different viewpoints and perspectives.” This requires some unlearning of the traditional ways of doing things and means leaders must let go of the construct of ‘hero leadership’. “Organisations can prepare by providing an adaptive, learning environment,” she says.

Powell believes that new mindsets can emerge in a culture that permits people to experiment, to make mistakes in the context of trying something new, and to be open to being challenged, seeing that as a growth opportunity, rather than a threat.

AI MUST SPARK A REVOLUTION

Renowned astronomer Professor Sun Kwok is the former Dean of Science at the University of Hong Kong (UHK) and recently wrote in the journal Nature about the success of UHK’s approach to science foundation courses.

Kwok says most universities still expect students of STEM to memorise facts delivered by teachers and practise mathematical exercises so they can do them speedily in exams. “These practices are wasteful and ineffective in today’s world. Computers can do these tasks better than we can,” he told the South China Morning Post in October 2018.

“Leaders in modern industries are demanding a new breed o graduate who can think and learn, not just perform assigned tasks,” he said. “Our goal is to provide our students with a set of skills that would allow them to enter and be successful in a wide variety of professions and careers, not just in the narrow subject of their major.”

Science students at UHK now learn new non-discipline based subjects designed to help develop broader perspectives, perform critical assessments of complex issues and appreciate diverse cultures. “They were aimed at developing intellectual skills that are difficult to replace with machines,” Kwok explained.

STUDY SNAPSHOT

Charles Sturt University’s Bachelor of Technology/ Master of Engineering (Civil Systems) degree designed by Professor Euan Lindsay, has been cited by Massachusetts institute of Technology (MIT) as a global leader for its innovative structure. Students spend four of the degree’s five -and-a-half years in year-long, paid placements working as cadets.

The course began in 2016, and real-world experience occupies the majority of course time. Students link their learning to work, presenting a portfolio of projects that are assessed against learning outcomes. “We put students on placements where they see the conseque3nces pf their actions and understand what it’s like to live with them,” says Lindsay. “We aim to produce highly skilled, entrepreneurial engineers who are equipped to step straight into the industry or start their business.”

WHY LEARNING HAS TO CHANGE… AND FAST

Organisations are demanding better-prepared graduates who have connected with workplaces during their degrees and know what is expected from them when they start work. University students are demanding more purposeful courses. We ware in an age where thy want method, not content, deep learning, not light summaries.

School students want to embrace education, they want flipped classrooms where learning is active, not passive, they want role-plays, problem-solving, discussions and team-based learning.

Teachers want to be supported in developing new and innovative ways to teach, to engage with their students ‘future employers and to stay relevant and exciting in a fast-changing world.

Maximus discusses what this change looks like…

“Currently there’s not a true partnership approach between higher education and corporate. Universities think it’s enough to have industry involved at the end of the state, ding all the teaching until there’s a six-month placement at the end, and interaction with industry isn’t embedded in their way of thinking, nor has it been traditionally encouraged or rewarded. Education and employment are no longer linear. Lifetime learning will require an ongoing interaction between universities, organisations and students.”

Dr Nora Koslowski, Associate Director at Maximus

“Traditional school curriculum, teaching to pass exams rather than learning skills for the future, is not just working. Universities are focused on research and working in isolation – it’s time for all educators to be more collaborative with industry. It’s also time to ask industry to step up – and help develop the leaders of the future.”

Mark Sowden, Director at Maximus

This article was originally published in the 3rd edition of M Magazine, an exclusive print magazine aimed at inspiring and driving change through Australia’s executives and heads of HR.