Trust is critical to being responsive, adaptable and innovative in a rapidly changing context. German sociologist and author of the 1979 book Trust and Power, Niklas Luhmann, noted that in the absence of trust, people would not even be able to get up in the morning. When trust in fellow humans, in basic infrastructure, in the wider institutions that support and govern our existence is so fundamental, it stands to reason it will be required for us to achieve the extraordinary. Trust is the tensile strength, the confidence in the integrity of people and things, that allows us to step into the unknown, or tackle the seemingly insurmountable.

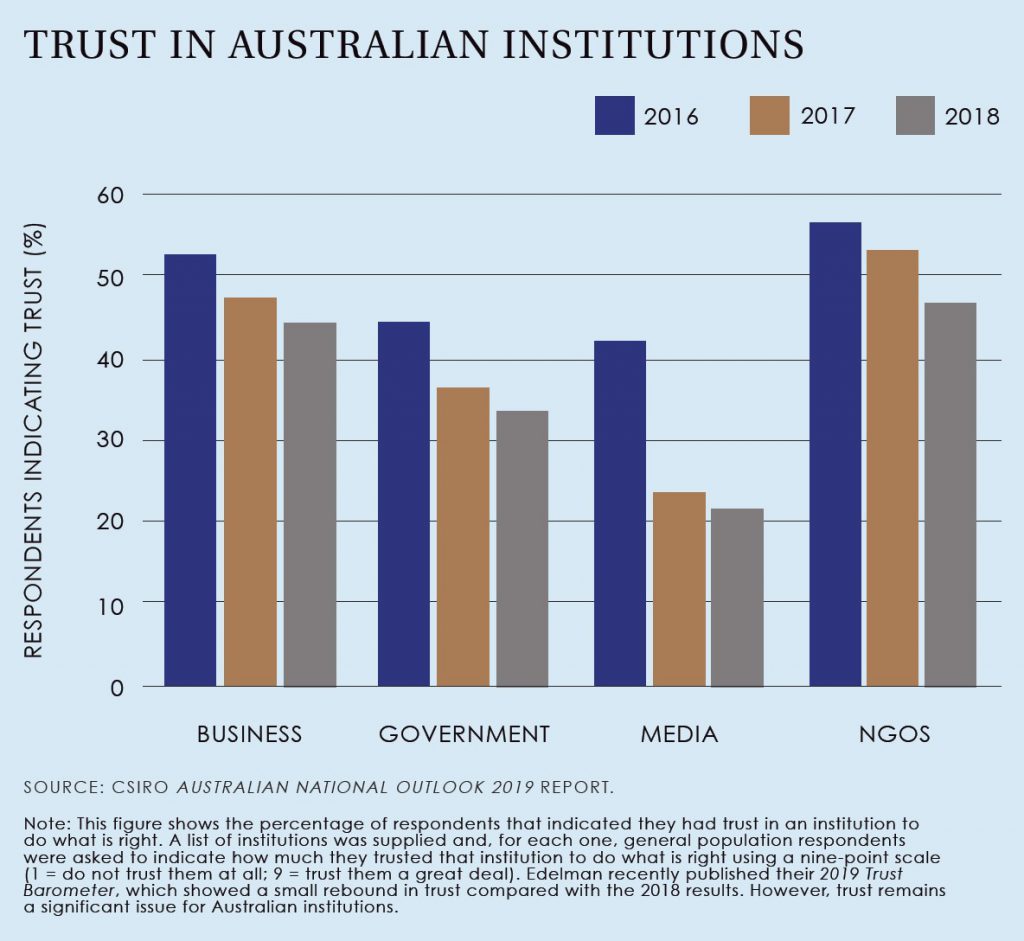

The importance of trust has recently been illustrated, yes, by the failures revealed in the Hayne Royal Commission, but also by the way it has entered every discourse and become a metric for our current and future health. Consider the annual Edelman Trust Barometer which in 2019 tapped 33,000 respondents in 27 countries for their level of trust in institutions, and the fact that CSIRO’s second-ever Australian National Outlook (ANO), published mid-2019, prioritised the rebuilding of trust in Australia’s institutions as instrumental to achieving an “inclusive, resilient and prosperous economy”.

James Aris, Head of Innovation, Offerings and Marketing at Maximus, highlights climate change as a macro example of how, despite being faced with overwhelming expert evidence, a lack of trust impacts institutions’ overall capability and impetus to act. “We’re seeing a breakdown in people’s social contract with institutions and expertise as a whole, driven by decades of abuse of trust. A structurally sound social contract is critical to drive appropriately transformative and positive action,” he says.

Peter Chamley, Executive Chair in Australasia of the respected engineering and infrastructure design company, Arup, says Climate Strike and related protests, of which he notes he is a strong supporter, are another measure of the breakdown of trust between people and institutions. “Governments are failing us in not listening to the people, and not taking a longer view to really address climate change and its many impacts.”

Although Australian respondents to the Edelman Trust Barometer recorded a modest increase in trust year-on-year across all categories of institutions – business, government, media and non-government organisations (NGOs) – only business (52 per cent) and NGOs (56 per cent) cleared the 50 per cent distrust barrier to achieve a ‘neutral’ rating. (A true relationship of trust is defined by a rating of 60 per cent or more.) Our low level of trust, says CSIRO’s ANO 2019, “threatens the social license to operate for Australia’s institutions”.

LICENSE TO DRIVE THE ECONOMY

Dr Kieren Moffat, chief executive and co-founder of Voconiq, a CSIRO spin-off (see over page), says that trust is fundamental to an institution’s social licence to try new approaches – to innovate. He says 10 years of accumulated data gathered in a dozen countries has shown “trust is central to the relationship between a company or an industry and the community it interacts with”.

“Trust acts as this vehicle that translates experience and expectation into acceptance,” explains Moffat. One of the outcomes of a trusting social contract built over time, he says, is that “you have more benefit of the doubt when things go wrong – people don’t immediately jump to the conclusion that it’s through negligence.”

Voconiq uses scientifically gathered insights to inform business practice and development, with the aim of strengthening social license and enriching the understanding and experience of all stakeholders in an enterprise or project. “One of the things that’s interesting to me,” says Moffat, “is that those companies that are able to build trust inside the building, within their teams, are able to build trust most effectively outside the building.”

Vanessa Gavan, Founder and Joint Managing Director of Maximus says that today’s employees, customers and the public in general expect more transparency from corporate leaders than ever. Communicating values with candour, conviction and integrity is essential to gaining trust. “We trust what we know,” says Gavan, “and if we never allow people to really know us, we can never really expect to be trusted.”

CO-CREATION: AN INCLUSIVE MODEL FOR INNOVATION

At Horizon Power in Western Australia, Chief Executive Stephanie Unwin knows exactly what this means. When Unwin began her role in March 2019, she set about clarifying the energy provider’s mission, values and objectives, by consulting with its 400-plus far-flung employees. Horizon Power’s vast service area covers 2.3 million square kilometres in WA, with various small concentrations of population in tourist towns, mining camps, indigenous communities, regional centres and remote agricultural properties.

Operating in one of the most disrupted industries in the world to provide enabling electricity that powers the varied ambitions of Horizon Power’s constituents, Unwin embarked on a schedule of travelling to, and with, regional customer managers and service staff to better understand their challenges and the communities they seek to serve. “A core value to me is creating a shared vision. In order to do that, you’ve got ask your people, who are really the most insightful of anyone you could draw upon, ‘What is it that we ought to be doing? And how should we be doing it?’”

Horizon Power’s refreshed guiding principles have been developed from the inside out. “The first thing we stand for is community involvement, so we’re not just going to give you something, we’re going to co-create and deliver something together,” says Unwin. “We seek to deeply understand what each of our communities want, and how we can, as the power system evolves over time, help to deliver into that.” Unwin says that Horizon Power’s guiding principles commitment to better outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders; a cleaner, greener shared environment; and regions first – “translate into what we define as helping our communities to thrive, and as a result having the social licence to operate”.

[FACT]

71% believe CEOs should take the lead on change rather than waiting for government to impose it.

Source: 2019 Edelman Trust

GETTING TO KNOW YOU FORMS THE BASIS OF TRUST

Part of being known is being prepared to express opinions on contentious topics from climate change to public policy. “Twenty years ago, leaders had no business having an opinion on whether gay marriage should be legalised, or taking a position on climate change,” says Gavan. “Now it’s an expectation. And that’s where the authenticity comes in: as a leader

you have to do the work and make sure that you really know what you are about and what you care about, because your choices and decisions must also be congruent with that.” The 2019 Edelman Trust Barometer: Expectations for CEOs found that 71 per cent of global respondents are looking to their employers for leadership around such issues.

If communication and congruence are at the heart of engendering trust, achieving the right balance between strength and vulnerability requires more complex judgement calls, says Gavan. Moffat has found in his work with Voconiq that clients who practise vulnerability in a safe place, within their own leadership teams, are more relaxed with expressing vulnerabilities in the broader realm, with stakeholders.

“Companies that don’t exercise those skills find it really challenging,” he says.

REINVESTING IN HUMAN POTENTIAL IS KEY

Moffat’s research also shows that many companies have, over the past 10 years, allowed their trusted standing with employees to deteriorate as they rush to meet other challenges: “They might have moved to short-term contracts or to employing more casual workers.” Such decisions, poorly managed, “really undermine the esprit de corps, the connections within companies, and people’s commitment to the organisation,” he says. Consequently, employees are “less likely to defend the company, to promote the company, or to talk in favourable ways in public about what it is doing”.

Trust is both an attitude and an action, notes Gavan. “While individual ‘willingness to be vulnerable’ is essential, there must be action that follows for trust to be made real. This is the choice to trust,” she says. “In conditions where there is perceived psychological or personal risk, that choice is unlikely to be made.”

Gavan believes that emotional commitment and discretionary effort are the greatest things an organisation can ask of its people. “You can’t ask for emotional commitment to your company,” she says, “unless you’re willing to give commitment in return; where everyone does their best work, to the best of their ability, and strives to create value in the organisation.”

Arup is known for its commitment to nurturing a diversity of talent. “We set out to find good people from whatever background and we’re clear that we want to be a diverse organisation,” says Chamley. “Our colleagues and people are at the heart of what we do. We are owned in trust, which is a form of employee ownership.”

The values of the company’s late founder, Ove Arup, pervade the global organisation of 14,000 ‘specialists’ working to “shape a better world”, as its website describes it. Chamley says Arup studied philosophy before engineering and had a ‘humanist’ approach to life: “His ethos of straight and honourable dealings and being very human in what we do was incredibly important to him and remains incredibly important in our organisation.”

“Trust-building is a dynamic process,” says Gavan. Typically, the focus is on the trustworthiness of the leader, however, an underestimated factor are the needs of individuals. The safety of each team member and their natural propensity to trust will precede their assessment of trustworthiness. Until information is available that supports trust, the trustor will base their decisions on their own internal dialogue. “Getting to the heart of the individual and matching follower needs with early leadership behaviours is what builds longer-lasting trust,” she adds.

Trust within Arup inspires employees to rise to any challenge, and the company is “trusted to deliver”, says Chamley of Arup’s relationship with its clients. “We started in Australia with the Sydney Opera House, which was a bit of a challenge,” he smiles over the phone, “but we never shied away from the complexity.” He says the way Arup responds to both the straightforward and the wickedly challenging, means that “clients continue to put their trust in us”.

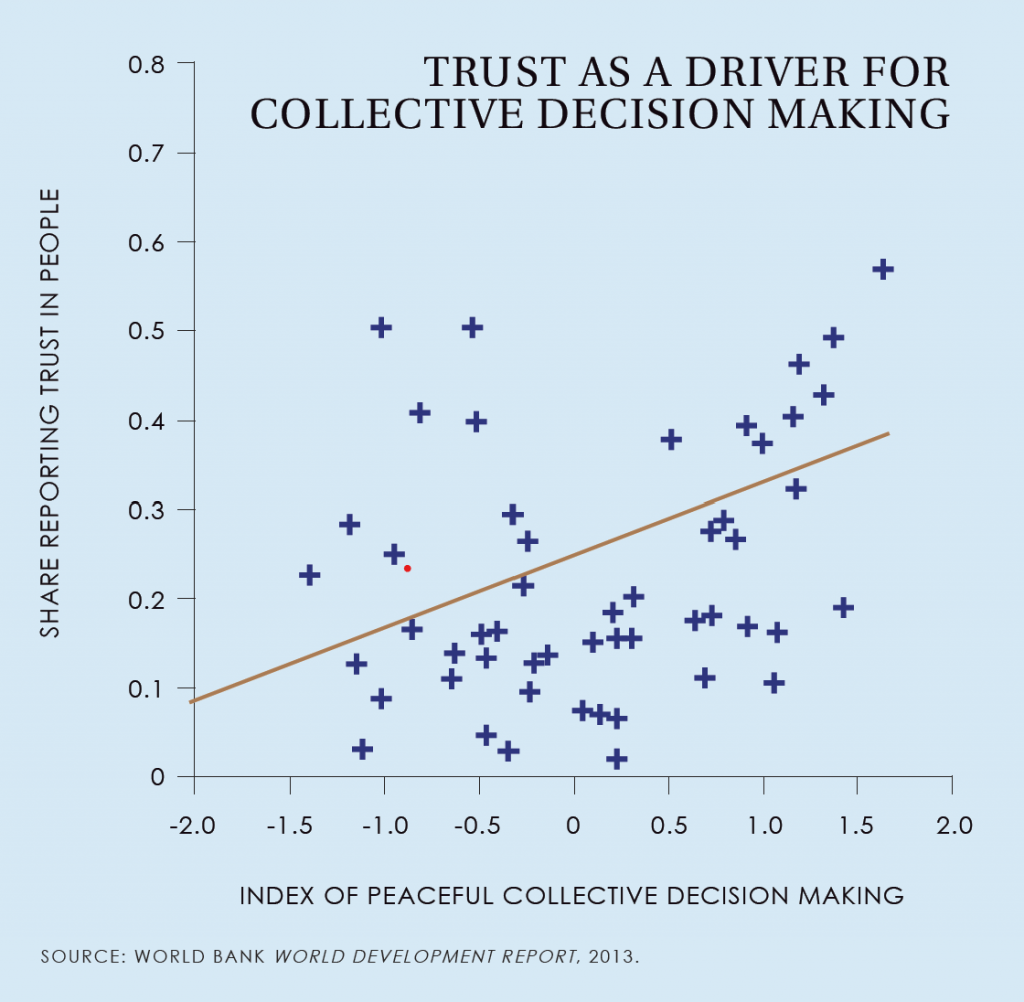

TRUST BUILDS CONSENSUS AND ENABLES ACTION

“Trust matters,” write the authors of the ANO 2019, because “it enables businesses to leverage their relationships with employees, stakeholders, regulators, customers and clients to invest and innovate, and it empowers governments to make necessary changes to policy and programs”.

ANO 2019 is designed to focus Australians, and particularly leaders in all sectors, on what it will take to achieve a Vision Outlook – the most positive future scenario of a thriving society and a robust, resilient economy. Trust is part of the identified necessary culture shift that will enable healthy risk-taking in Australia, and encourage engagement, curiosity and collaborative problem solving.

“What comes out of the CSIRO report,” says Gavan, is “if we want to be a nation that innovates better, that’s going to ultimately improve economic conditions for Australian organisations and our economy, we have to have a more exploratory nature and think longer range”.

Rebuilding trust with employees and the public will, perhaps paradoxically, confer greater freedom on leaders to test new paradigms and approaches and to act decisively. “Trust allows you to be more agile,” concludes Gavan. “It takes unnecessary process and protocols out of the equation because the people around you are enabling and supporting you. It’s critical to unlocking longer term thinking and growth.”

VOCONIQ: CSIRO’S TRUST SERVICE

In 2007, Kieren Moffat was mid-PhD and working as a leadership consultant to a mining company. Each day he would drive into the NSW mine site. One day, placards at the gate might say, “Mining is killing the earth”; the next, they read: “Get a job, you hippie!”

“This conversation between different groups in the community was much more interesting to me than what I was doing inside the fence, so I applied my studies and research to understanding that conversation and trying to facilitate a more constructive one,” says Moffat. Improving mutual trust and the social licence to operate could only benefit both groups, he reasoned.

Over a period of 11 years at CSIRO, Moffat and his team developed a system of voluntary surveys, and analysis of the resulting data, which shares scientifically proven insights between industries/governments/companies and communities.

Voconiq (which stands for “voice-connected IQ”) was formed in 2019 to bring the rigorously tested platform to market. The company’s first service, Voconiq Local Voices, is now working to give voice to community members all over the world.

While many companies realise they can no longer expect to simply maximise profits to shareholders without considering customers as community members, their approaches to conflict resolution and relationship building are still “top down. “There’s real work to be done, and that’s the space we operate in,” says Moffat.

Currently under development is a version of Local Voices specifically designed to give voice to Australia’s Indigenous people and other First Nation groups around the world. “It’s a long, long journey,” says Moffat, but “the Indigenous voice has real value, and if we can find ways to amplify it, that’s the start of building trust.”

This article was originally published in the 4th edition of M Magazine, an exclusive print magazine aimed at inspiring and driving change through Australia’s executives and heads of HR.