Thought leaders in the corporate world are reframing how machines can best be used to add value and deliver economic benefit, by flipping the case from artificial intelligence (AI) to intelligent automation (IA).

Where AI is feared for its perceived potential to increase efficiencies by displacing humans in the workplace, IA promises to augment and unleash essentially human talents. Yes, it’s toying with terminology, but redefining for IA promises to free people from drudgery and enable them to add value in uniquely human ways, so it’s important for leaders to make the conscious shift.

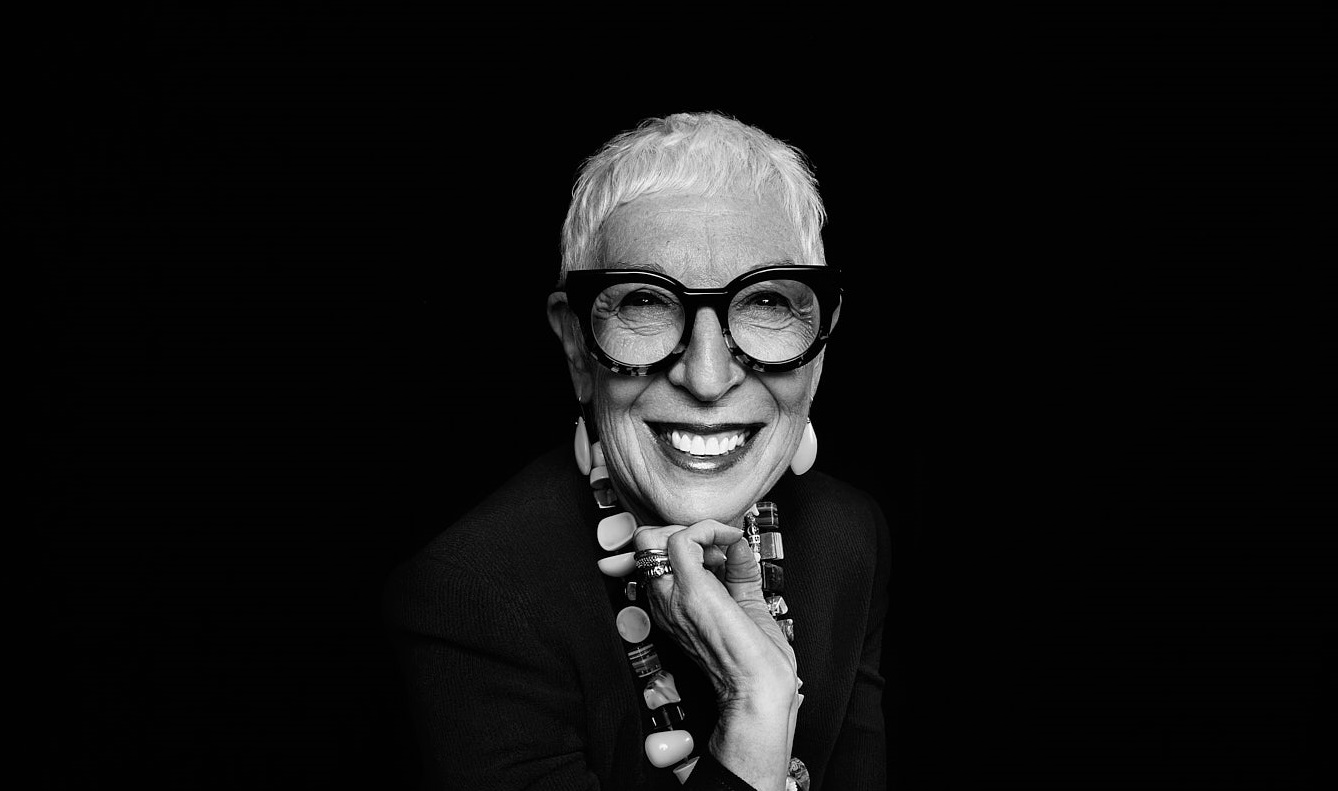

US-based technologist and organisational psychologist Muriel Clauson defines the least automatable human capabilities as ‘power skills’ – a much-needed upgrade, she says, from the often referred to ‘soft skills’. They include agile communication, critical thinking, innovative problem solving, recognising opportunities, leveraging information and experience to make better decisions, and seeing connections between systems and trends.

Clauson, who has for some years advised government and corporate leaders on workforce change, says “humans have so much incredible potential and we don’t come close to leveraging that today.”

The call is for business leaders and managers to add value in context: to engage humans in separating the aspects of their work that are stultifying, to design the automated systems that can best replace those tasks, and to redeploy people with the help of skills-development micro courses and mentoring – in more satisfying roles.

As part of this process, leaders may choose to tailor available software and hardware platforms to their company’s needs. And, where necessary, develop industry or company-unique technology solutions that take over the precise and repetitive tasks that don’t tap into human power skills.

The recent Maximus whitepaper, Curating Culture: Mobilising People in the Age of Disruption, called on leaders as architects of value within organisations to “allow people and teams the freedom to be curious and to innovate, by empowering them in processes and technology”.

Laura Sturt-Addicott, Associate Director at Maximus, welcomes the evolution of thinking from computers competing with humans for work, to machines assisting humans in their quest for more meaningful roles in the economy. “Leaders and managers need to reframe the concept of teams and individuals from being executors of tasks to becoming opportunity finders,” she says.

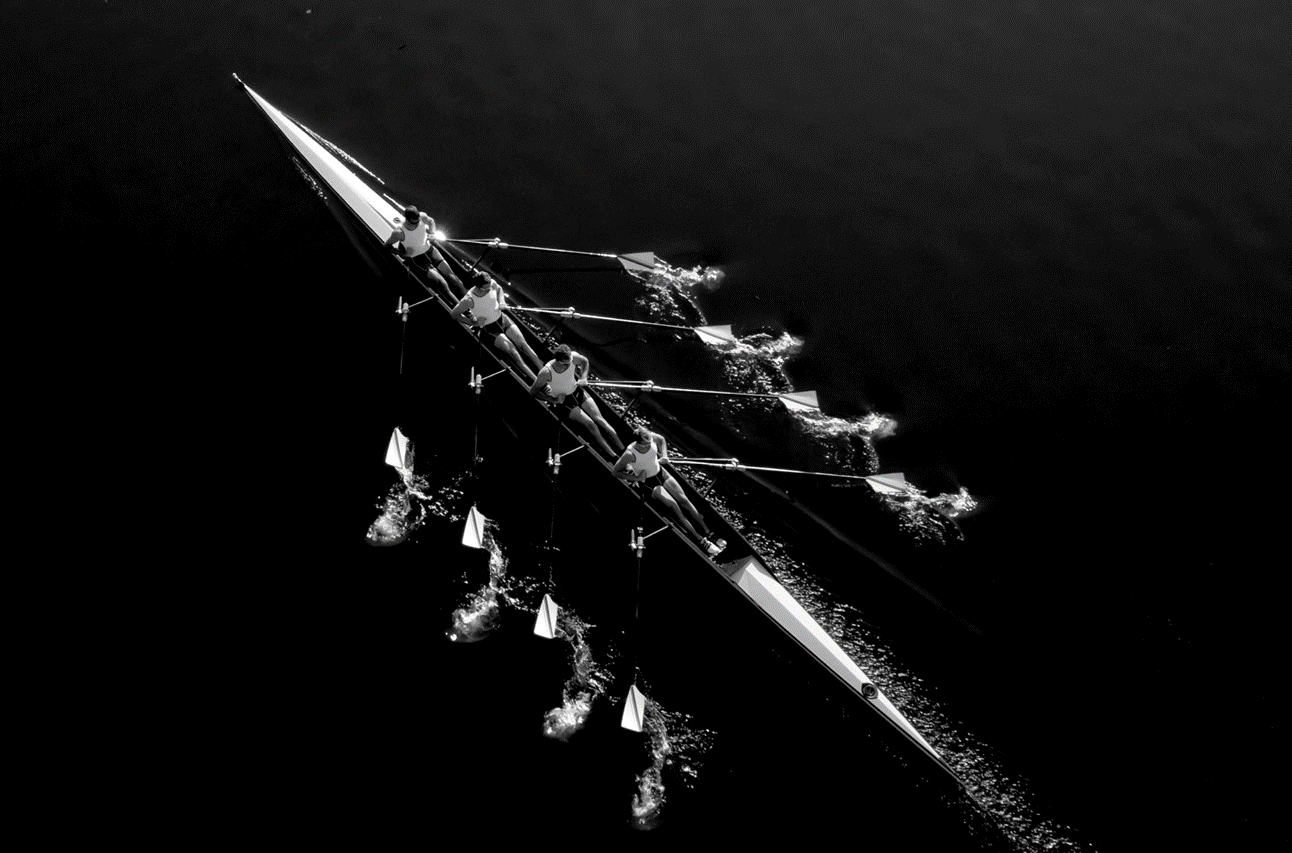

ORGANISATIONS DON’T NEED ANOTHER HERO

Another important mindshift is towards collective success. To leverage the collective thinking of diverse teams into novel solutions, managers need to focus on a ‘we’ rather than ‘I’ culture. “They need to reward for team-based outcomes, rather than for individual tasks,” says Sturt-Addicott.

In most scenarios, digitalisation is likely to offer solutions to a percentage of employee tasks, and the opportunity is to productively use the proportion of time gained to combine people’s accumulated and varied experience of their industry, coupled with their creative capacity, in new directions.

“The number-one thing I say to leaders who are worried about their organisations and how they need to prepare people for change, is to get serious about learning what people actually do in their jobs at the individual level,” says Clauson.

Clauson has formed a company, Anthill AI, to develop a digital platform that helps people and managers explore individual skills potential. “We have a cultural norm that nobody works in private. Anyone can access what someone else is working on at any point in the development process,” she says. “Our thinking is we don’t expect anyone to be perfect. We’re all learning as we go and sharing; no one is expected to be a genius. We end up with better results.”

Clauson’s approach requires leaders to create a culture where people are willing to embrace a digital mindset. This doesn’t mean leaders or their teams need to be experts in the technology, but that they be open to the possibilities of what can be created and enhanced by integrating technology into new work practices. Among the keys to this culture is that leaders provide opportunities for people to learn by increments as they test and try technology, as well as new ideas, in a psychologically safe environment.

RESHAPING BUSINESS MODELS TO MAXIMISE ROIA

Australia’s Digital Opportunity, a September 2019 report by AlphaBeta, calculated that Australia’s technology sector could contribute greatly to GDP if the country caught up to global leaders. It identified investment in technology platforms and the adaptation of business models to make better use of intelligent automation, as being crucial.

The report offers the notional example of a manufacturer that undertakes automation of a production line and deploys intelligent human capital to change up its product development and redesign marketing strategies. Such “marginal improvements”, says the report, “accounted for six per cent of the total economic value generated by digital innovation in advanced economies between 2000 and 2018”.

Maximus’s Curating Culture whitepaper expands on this concept, saying the conditioned thought processes of leaders must shift from modelling company strategies on what happened in the past. As architects of future value, they will redeploy human capital with curiosity and power to implement technology; this in turn can “foster strategic planning and articulation of value-creation around what could be”.

“Re-shaping business models to create value means leaders need to think differently,” says Sturt-Addicott. “At Maximus, we work to expand leaders’ thinking, to enable them to look beyond their own organisations and industries into new markets which tackle challenges differently.

We maintain focus on such opportunities by bringing international perspectives to Australia, through research and partnerships with progressive global thought leaders.”

A recent global survey, Easing the pressure points: The state of intelligent automation by KPMG in the US, cautioned that many organisations that have adopted IA are struggling to demonstrate significant impact from their investment. Most notably, this is because they have not incorporated the technology into the vision and purpose of the organisation, nor structured their teams and workflows to take advantage of the digital assistance.

To realise the full potential of automation beyond cost savings, organisations must incorporate change management at every stage of machine integration by investing in their most valuable resource: their workforce.

“There is a need for leaders to ensure they have a strong vision for their organisations, departments, teams and people they work with in order to be true value architects,” says Sturt-Addicott.

“We know that parts of people’s roles are going to be automated, that jobs will be different and both companies and employees will have to adapt,” says Sturt-Addicott. Where that lands in terms of reskilling or upskilling existing staff is still very varied in the Australian business landscape.

“Leaders need to think about automating responsibly and ask, ‘If I’m going to automate half of the work my team does, how do I build my people for the future?’‚” she says.

In a now-famous example of inclusive IA, Australia Post’s accounting services department challenged its team to identify ‘new pathways’ for managing the almost crippling volume of accounting tasks inherent in keeping track of services and products across more than 4300 post offices Australia wide.

After a successful pilot program using Automation Anywhere’s robotic process automation (RPA) system, AusPost automated 25 processes. The resulting restructure of workflows, and annual saving of 18,000 hours, enabled team members to “reinvest their time towards improving the experiences of customers”, a report on the project states.

Steven Morris, Head of Accounting Services at Australia Post commented that, “leveraging RPA, our team members were able to identify new ways to automate and scale, contributing to the growth and productivity of the entire department”.

Retraining can be expensive but firing one sector of the workforce in favour of rehiring fewer, more appropriately skilled workers for new roles may be more so. The labour market can also be left in tatters by employers chopping and changing: “Cutting talent that no longer suits the needs of an organisation and hiring new talent can lead to massive skills gaps in the market,” says Clauson.

AUTOMATING FREE OF BIAS

As a board member of the not-for-profit organisation Humans for AI, Clauson also advocates for diverse human input into the automated systems we choose to design.

For architects of value within organisations, she says it’s critical they involve employees in the development of their new automated ‘colleagues’. Bringing a variety of people into the process of designing automation tools is the only way to create more inclusive AI, says Clauson.

Kriti Sharma, Vice-President of Artificial Intelligence at software giant Sage, said in an April 2019 TED talk that more relevant than our fear of robots replacing us at work is the decisions AI can make about us.

For example, AI decides that a person named John is likely to be a better programmer than someone called Mary. Why? The AI picks up the fact that as an employer you hire more men than women for tech roles. “From that, the AI learns that men are more likely to be programmers than women, then it’s a very short leap to ‘Men make better programmers than women,’” Sharma explains.

Future society relies on us ensuring at every stage of automation design that it aligns with and reinforces the values and ethics we want to pervade our lives.

To do that, we need to involve people with varied backgrounds, ages and sexualities in the creation of automated systems… Ideally, they will not all be coders. Some may be storytellers, domain experts, problem-solvers, behavioural scientists – their perspectives further broadening the inclusiveness, creativity and empathy that informs our automated assistants.

Sharma says that given diverse input, AI can be used to make the world a more equal place, delivering services and opportunities that don’t yet exist to people isolated by circumstances or geography; and architecting positive value into a richly human future society.

CUSTOMER SERVICE: TECH-ING IT UP A NOTCH

Victor Dominello, the NSW government’s first Minister for Customer Service, is a passionate advocate of digitalisation as a humanising tool.

He likens the conditions in agencies that handle high volumes of information and regulation without the help of automation to forcing people to work in an ‘iron lung’; whereas, given “a good working environment, enabled by smart technology, it’s a joy to serve”, he says.

The minister of a growing department in terms of increased service centres and employee numbers, Dominello says, “It’s not about job losses, but around job creation in things people do best – like people engagement. The human aspect is critical. AI and technology can only go so far. We need to ensure that people are there to assist people.”

Six years ago, the NSW government embarked on its digital strategy to fast-track service transformation. Since then online digital services, such as simplified car registration, a business concierge to help constituents navigate the regulations and requirements for setting up new businesses, and MyServiceNSW which streamlines customer transactions with government, have increased Service NSW customer-satisfaction rating to 97 per cent*.

In 2017, Service NSW was awarded 24th place in the Australian Financial Review’s list of Australia’s ‘50 Most Innovative Companies’, and following its re-election last March, the Berejiklian government doubled down on digital transformation with a focus on deeper cultural change.

Dominello believes every aspect of public policy making and service delivery can be improved by intelligent automation, however cultural change, says the minister, is the hardest part of digitalising any organisation. In September he accelerated the state government’s internal systems for funding tech projects by radically consolidating the number of ministerial committees that run the state to three: Cabinet, Treasury and new customer-focused committee dubbed the Delivery and Performance Committee (DaPCo), which is chaired by Dominello and the Premier. DaPCo will interrogate applicants for tech funding on the data architecture of the project, the digital design and the customer lens. If they satisfy committee criteria, projects can go straight to Treasury and request funding based on return on investment or a cost-benefit ratio.

Leaders and employees may understandably be fearful when they’re uncertain of the future, says Dominello, but the do-nothing response will lead to them falling ever further behind.

“By leveraging technology to frame and speed up everyday decision making – and disseminating the mindset for their teams to do the same – leaders will find themselves capable of getting up and out, while also increasingly adding value at an organisational level,” says Sturt-Addicott. “The single worst thing that can happen in these situations is that leaders narrow their focus on their silo and fail to recognise the organisational advantages and value opportunities of embracing technology.”

This article was originally published in the 4th edition of M Magazine, an exclusive print magazine aimed at inspiring and driving change through Australia’s executives and heads of HR.