Behavioural economics, it seems, is now everywhere: used by governments to boost retirement savings, by marketers to entice consumers, and by investment managers to encourage better financial decision-making.

Director of Maximus, Mark Sowden, helps organisations develop and implement leadership frameworks and manage change, applying growth mindset strategies to help leaders and individuals redefine their approaches to work, culture, leadership, organisational design, performance and rewards. Sowden’s strong background in behaviour change gives him an acute understanding of the key insights offered by behavioural economics.

“The field is growing rapidly and we now see a shift away from the original application of behavioural economics concepts to customer and marketing functions being applied to resolve leadership challenges,” Sowden says.

“Leaders are realising that engaging behavioural strategies, like ‘nudging’ tactics to create a feedback culture or a high-performance culture in their teams, will deliver better results than they would get when trying to shift those types of culture dynamics internally.”

DEFINING BEHAVIOURAL ECONOMICS

The current craze for behavioural economics can be explained in just two words: it works.

“You could describe behavioural economics as solving all the things that traditional neoclassical economics gets wrong,” muses Australian psychologist Sam Tatam.

Now based in London, Tatam heads up strategy for Ogilvy Consulting’s Behavioural Science Practice, the world’s first and largest behavioural science team within a global creative network. Everything from lifting retirement savings simply by changing employer plans from opt-in to opt-out; to improving tax compliance by requiring taxpayers to put their signature at the top of their return; and the old supermarket favourite, putting sugary treats at a child’s eye-height next to the checkout, is proving successful. Marketers have applied certain behavioural principles to their strategies for over a century, aware of their influence on consumers.

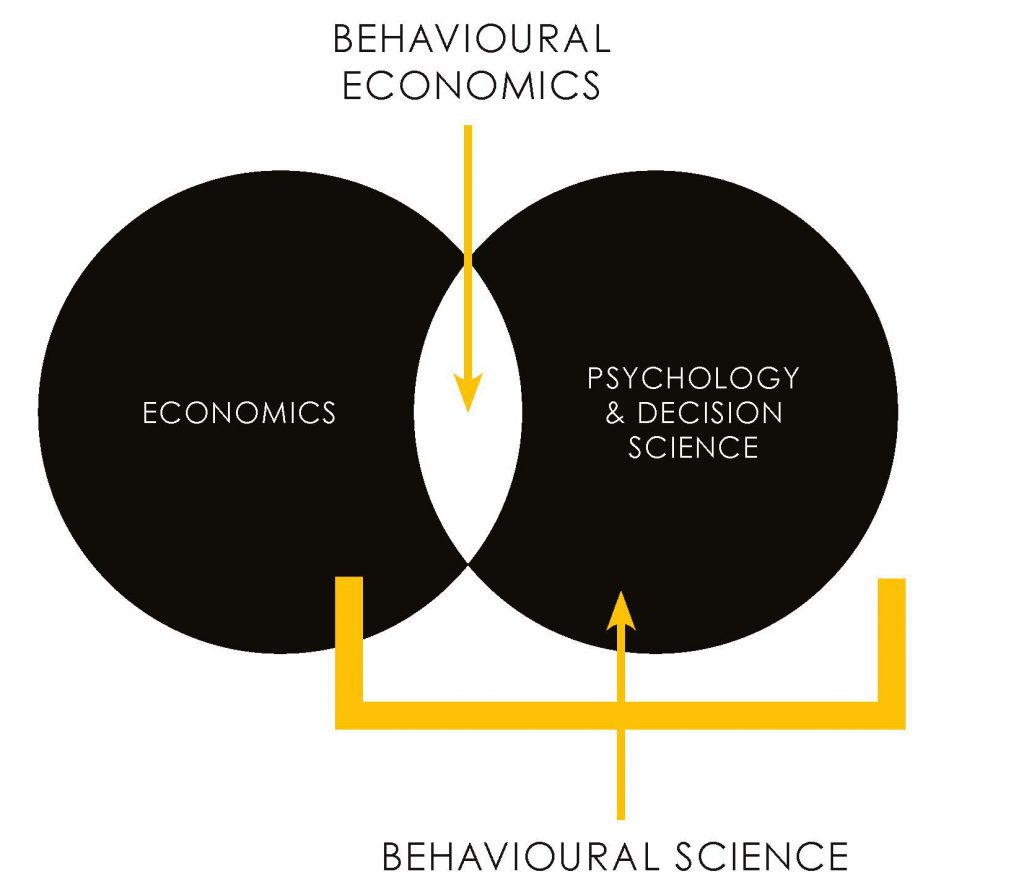

Behavioural economics takes this a step further, drawing on the rich findings from decades of research into human behaviour, and applying this to our analysis of market interactions to help us understand how and why humans make financial decisions.

The earliest economists – Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill and John Maynard Keynes – all brought aspects of psychology into their economic theories.

This changed by the mid-20th century, when leading economists such as Friedman and Samuelson promoted ‘expected utility’ theories, assuming that people have rational beliefs and make logical decisions according to informed self-interest.

But the pendulum had swung too far and behavioural economics came to the fore, with founder Nobel Laurette Daniel Kahneman, using psychological insights to account for the often-irrational financial decisions of humans, both individually and en masse.

SO HOT RIGHT NOW

Behavioural economics can provide effective strategies, where even the smallest of interventions can encourage people to change their decisions.

“Language helps people to conceptualise things,” explains Tatam. “The frame of ‘economics’ is really powerful in enabling people to embrace concepts that in the past were considered softer sciences, like social psychology, that might previously have been considered a bit more whacky in C-Suite discussions.”

“Putting those concepts in the frame of behavioural economics makes them feel more tangible and predictable, like the laws of supply and demand,” he says. But the key difference is that humans aren’t rational, utilitarian actors who only do something if they stand to gain immediate benefit in return, navigating the world with perfect information and perfect trust and making decisions accordingly. “Human behaviour is decidedly irrational at times, there’s elements of our behaviour, like altruism, where we don’t stand to gain any immediate rational benefit – yet we still do it,” Tatam says.

Behavioural economics helps make sense of this. It tends to focus a lot on financial decision-making, and seeks to find explanations for actions that, on the surface, seem less than rational, and to understand the nuances of human decision-making that subvert neoclassical economic models.

As a psychologist, Tatam brings a slightly different slant. “My work tends to focus on the behavioural science side of things,” he says. “I see my role as coming up with solutions to help people make better decisions.

”Cost-effective techniques that tap into human psychology can be more powerful than more expensive, strictly economic approaches, Tatam explains. “The right small changes can make significant differences,” he says.

OGILVY’S BIG BEHAVIOURAL VENTURE

At Ogilvy, Tatam works alongside the company’s vice-chair Rory Sutherland, who championed behavioural economics at the renowned UK agency more than five years ago. The agency has since captured a large range of high-profile clients including The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Facebook, American Express and Ford.

Tatam’s own foray into behavioural economics began at Ogilvy’s Australian office, where he was a brand strategist before heading up the company’s behavioural science team. Tatam sees his role to deliver best-practice, but also “to forge discovered practice, to find new ways in which we can apply this thinking.”

These include uncovering some very nuanced and fun ideas, he says, and some useful insights such as: question everything, don’t oversimplify.

Ogilvy’s behavioural science practice has given the agency client opportunities that may not have otherwise come to the business, Tatam adds. “We’ve grown over the last six or seven years quite organically, with projects where either traditional communications approaches haven’t been working or the traditional advertising function just wouldn’t address them,” he says.

Examples include behavioural-based safety programs, optimising call centre scripts to retain customers and close sales, and even helping businesses develop tools and infrastructure to protect from bias in recruitment promotion and remuneration decisions.

“We have a role where we can apply creative thinking to solve some of the world’s biggest challenges,” Tatam says. He points out that the growth in the importance of behavioural economics has also enhanced Sutherland’s reputation. “He used to be invited to marketing conferences, now he’s invited to Number 10 [Downing Street].”

FROM MARKETING TO LEADERSHIP

It’s difficult to change the way people think, says Professor Ziv Carmon, a world leader in the field, so behavioural economics takes a different approach. “Research shows that by changing the environment in which people make their decisions, you can change their actions. Behavioural economics offers a wonderful combination of two benefits which leaders love,” says Carmon. “It provides solutions or levers that are both very powerful, and very cheap.”

Carmon left a successful business career in the late 1980s to study behavioural economics under Kahneman, at the University of California, Berkeley. His own research in the field is widely cited. He moved from Duke University to INSEAD, one of the world’s leading business schools, where he now serves as Dean of Research.

Carmon says that there are many new and interesting applications of behavioural economics in the workplace.

“For example, Intel conducted a study with a behavioural economist to help work out how to motivate employees to increase productivity during peak times,” he says.

People were randomly assigned one of four different short-term rewards for productivity increases. The rewards were either: a cash bonus; free pizza; a choice between the cash and the pizza; or a compliment by their boss. Then, the reward was withdrawn.

The outcomes went against expectations, Carmon says. The short-term rewards of pizza and compliments were the most effective. More importantly, when the reward was withdrawn, those who had received the financial reward showed a substantial drop in productivity.

“Receiving a compliment from their manager, which is, of course free, both boosted productivity and didn’t reduce it after withdrawal,” Carmon says, adding that the outcomes went against common practice (and maybe even common sense!).

“What is interesting about this is that if you surveyed managers, most would throw money at the problem rather than the more effective and cheaper solution of just giving employees a good word.

”There’s a few things going on in this scenario, Carmon explains. “While most of us say we work for money, we also work for other things like a sense of self-value and meaning,” he says. Also, once people receive additional payment, its loss is felt more deeply, even when anticipated, he adds.

The lesson for leaders: people are complex, and their self-esteem plays an important role in their contribution in the workplace. Carmon says that leaders can use the insights from behavioural economics to make more effective decisions, and that awareness of things that impede effective decisions – like emotions, prejudices and biases – can help.

“By changing the context in which people decide, you can change their behaviour.”

– Professor Ziv Carmon

LESSONS FOR LEADERS

Sowden reasons that behavioural economics offers a range of strategies that businesses can adopt to help them operate more smoothly and make more effective decisions. For example: the traditional organisational psychology approach to a change process, such as a team restructure, often looks at the phases people go through to get to acceptance, so they are willing to take the next step and go through the change. “Those traditional ways take the human factors into account and try to enable behaviour change as a result of it,” he says. “But they don’t actually create a different context to make that process easier – which is what a behavioural economics approach can provide.”

Behavioural economics gives people an extra ‘lens’ through which to view the impending change, says Sowden. “They can frame a change so that it is more easily enabled within their teams,” he explains. “Leaders can explain the change both from the rational, unemotional point of view and from a data and context point of view – but they’re also doing it from a psychology point of view.”

Sowden believes that behavioural economics ‘nudges’ that encourage people into making desired choices can be a useful tool in organisational change management. “Not only can these accelerate and provide more sustainable change, I think that behavioural economics can also help shift habits and values as well.”

Leaders are increasingly engaging with the real-world findings of behavioural economics to enhance their own effectiveness, bring out the best in their team, and to lift the performance of their organisations.

A huge amount of effort and thinking goes into every article we publish and we’d like to say thank you to Fran Molloy for contributing to this article.

This article was originally published in the 2nd edition of M Magazine, an exclusive print magazine aimed at inspiring and driving change through Australia’s executives and heads of HR.